NewmarketToday.ca brings you this weekly feature about our town's history in partnership with Richard MacLeod, the History Hound, a local historian for more than 40 years. He conducts heritage lectures and walking tours of local interest, as well as leads local oral history interviews. You can contact the History Hound at [email protected] or on the History Hound Facebook page.

It seems a coincidence that the birth of the tiny settlement that we would later call Newmarket would coincide with the beginning of the 19th century, when Timothy Rogers brought 40 families from the northern American states to the Yonge Street area in 1801.

Rogers, who himself came from Vermont, led his relatives and friends from the hardship and oppression following the American War of Independence to land stretching north along Yonge, part of a series of 200-acre land plots granted to him by the Crown.

The new settlers were mostly Quaker in origin — my relatives, the Lundys, were among this group. Their prime focus initially was securing food and shelter.

At the time, the area that would eventually become the village of Newmarket was a strip of land along a stream that was one concession east of Yonge, the old Main Street trail. Many say this old Aboriginal trail pre-dated Yonge by centuries.

The topography of the area was high land on both sides of a stream that ran through the valley. If you stand facing east at Yonge and Millard, you can still see this topography, even with all the development over the last 200 years.

It was here that Joseph Hill dammed the stream and erected a gristmill on the west embankment and, later, a sawmill on the east side. The first bushel of grain was ground in December 1801. These mills would provide the flour necessary for the sustaining of life and timber for shelter.

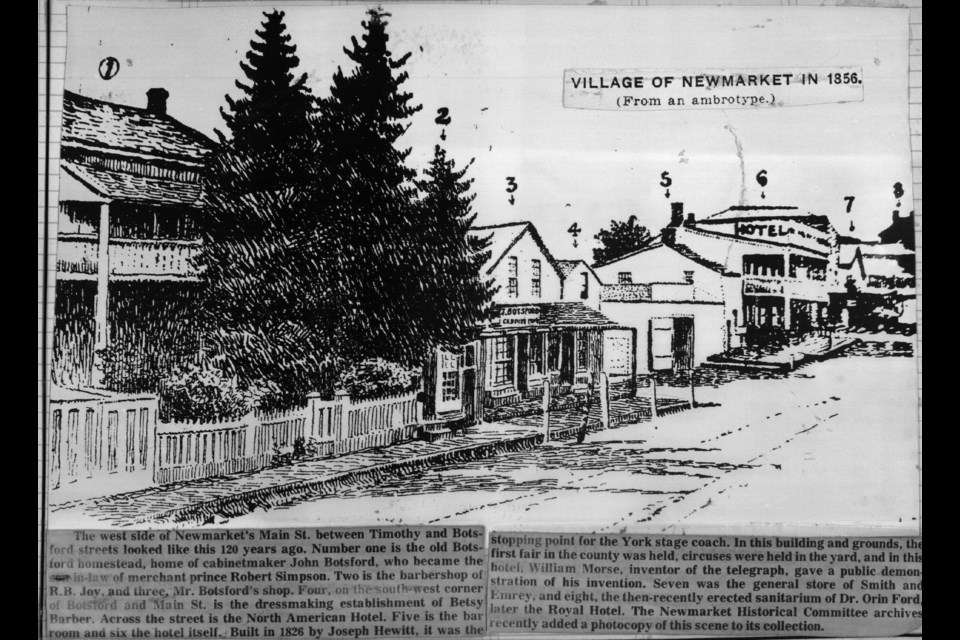

This area would become the nucleus for our embryo community. Soon there were shops and dwellings on both sides of the old Indian trail that led north from the mill site. By 1820, there were 14 buildings to accommodate the needs of the settlers, including shops for the blacksmith, tailor tanner, cobbler, cabinetmaker, saddler — all the trades needed for life in the wilderness.

Timothy Millard’s farm (lot 94) extended over the main street and as the population increased, he would create a series of streets running eastward, naming them Timothy and Botsford streets, and parcelling off lots for dwellings. Further north, New Street was opened in 1866, later renamed Park Avenue.

The mid-1800th century saw a dramatic change with the arrival of the railway. This was the end of the stagecoach era and rapid transfer of goods and produce accelerated to the major markets. In 1858, the settlement was incorporated as a village with its own government.

All the buildings were of wood construction and fire was a constant menace. A bucket brigade was formed in 1853, but it had little impact in combating the hazards. Eventually, all wooden structures were destroyed by catastrophe, depreciation or demolition — no buildings prior to 1862 remain.

It seems by providence that the Stickwood brickyard on Prospect Street started producing bricks and, from that time, most new buildings were built with brick. I have covered this period in my previous articles on Henry Cane and on the history of the fire brigade, which you can read on NewmarketToday at your leisure.

On Dec.6, 1862, a fearful fire broke out at 3.30 a.m. on the east side of Main, about where Robins pharmacy is now located, and jumped rapidly past Timothy, half-way to Water Street. In 1871, the buildings on the west side of Main, south of Botsford, were destroyed and, in 1875, the west side south of the former Post Office was levelled with little salvage. On Oct. 13, 1871, the gristmill at the pond was completely burned, along with nearby buildings, including the first building in the village built by Joseph Hill.

After all this destruction, two and three-story buildings were constructed using Stickwood bricks, with internal firewalls between each individual unit. Most are still standing today.

Despite many modifications, especially at street level, the character of the upper levels can still be recognized as a semblance of the original facades. These facades were originally in the Regency, Victorian and Italianate style with heavily bracketed cornices and paired round-headed windows. The storefronts had small glass panels with molded dividers. Large plate glass panels were not yet used. A few of the storefronts had ornate canopies over the walkways and supported by columns at the edge of the road.

A bylaw was passed in 1893 to prohibit wood buildings on Main from Water to Queen streets and, in April 1897, another bylaw defined fire protection regulations to conform to the demands of the fire underwriters.

The area between Timothy and Park was the central business section, with several smaller stores extending south to Water. These stores carried a large selection of commodities, primarily dry goods and groceries; some of them sold whiskey and wine as a stock item. Then, the businesses changed partnerships and ownership often and were in a continuous state of flux.

For example, in 1858, Robert Simpson, the future Toronto king of merchants, was a partner with William Trent in general merchandise until 1862. Then he continued on his own from March until May in a store at the northwest corner of Main and Timothy. On May 14, 1862, he formed a partnership with Moses Bogart under the name Simpson & Bogart. In 1871, Robert Simpson left Newmarket for Toronto, where he established the great mercantile empire at the corner of Queen and Yonge.

A milestone was reached Jan. 1, 1881, when the village was incorporated as a town. There was no electricity, telephones, running water or sanitary system. The streets were unpaved, muddy in wet weather and dusty in summer. They were not hard surfaced until 1921, when sewers were eventually laid. Heating was by wood stove and lighting was by kerosene lamp, which had recently replaced the candle.

In the last decade of the 1800s, this all began to change, with electricity, telephones, domestic water and even automobiles introduced. (See my related article on Henry Cane).

The electric railway was built for rapid access to Toronto (see related article below) and the community was prepared to enter the 20th century. The population had grown to 3,000 since emerging from the wilderness and there were six churches, two public schools, a separate school, a high school and a public library, two chartered banks, two extensive industries, a pickle factory, flour mill, cabinet makers, foundry, and brewery, but we were still firmly agriculturally oriented.

The 19th century ended much like it had begun. It was the end of an era when William S. Cane, our first mayor, passed on Jan. 4, 1899, ending a long career devoted to the progress of the community as a merchant, manufacturer, public servant and humanitarian. (See the related article on William Cane below). It was also the end of the Victorian Era when Her Majesty Queen Victoria died in January 1900.

Come out and hear part two of the Main Street saga, the years from 1900 to 1945, at the Newmarket Public Library Jan. 23 at 7 p.m.

I wish you all a joyous and profitable 2019 and stay tuned to NewmarketToday for more sorties into our past in 2019.

Sources: The History of Newmarket by Ethel Trewhella; The Newmarket Era; The Memorable Merchants and Trades by Eugene McCaffrey and George Luesby; Maps by George Luesby