This is the first of a two-part examination of the history of gas stations, beginning with their arrival in Canada and our town. In part two, I will look at back through history at our iconic Newmarket gas stations. I am sure you will remember your local gas station from your youth and have noticed just how much they have changed over the years.

The first recorded gas station in Canada was established by Imperial Oli in Vancouver at the corner of Cambie and Smithe around 1907.

It consisted of a 59-litre kitchen water tank with a garden hose attached to the side of it. This early station was a simple, open-sided shed of corrugated iron, and the gas got into vehicles' tanks through that hose.

The appearance of the gas station, as well as garages and parking lots, came after the introduction of the automobile into Canada in the late 19th century.

Motor vehicle registration figures would appear for the first time in The Canada Yearbook of 1916-17. It was in this year that the Yearbook accorded motor vehicles a new status as the most important means of transportation in Canada.

The introduction of the car created a need for new building types and designs. Men of vision like Edward Boyd, who maintained a stable next to the Metro Rail station on the north side of Botsford Street foresaw garages replacing stables and parking lots replaced hitching posts and he made the shift.

In 1904, 535 cars were registered in Ontario; in 1916, it had grown to over 54,375. Canadawide that year, there were 123,464 vehicles registered. By 1922, that figure had reached 513 821, and in 1928, there were 1,076,819 registered vehicles.

The popularity of the automobile created a rapidly expanding market for gasoline and gas stations. The evolution of gas station architecture reflects both the changing functional requirements and cultural attitudes.

At the beginning of the 20th century, few places sold fuel and drivers often had to obtain it from oil distribution terminals on the outskirts of communities. There, cans were filled from bulk tanks and manually funnelled into vehicles. These cumbersome manual fuelling methods proved inadequate to meet the rapidly increasing demand, prompting the development of more sophisticated pumps and underground storage tanks.

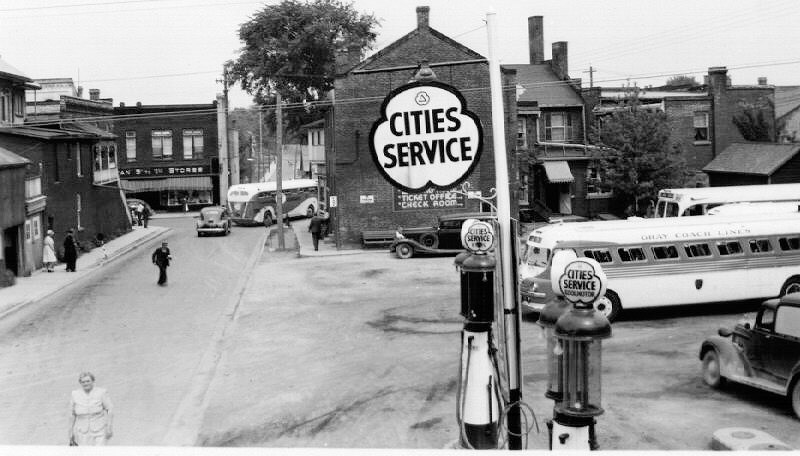

The early gas stations were often located with bicycle shops, hardware and grocery stores, businesses that carried household petroleum products and expanded into gasoline sales. The curbside station was an important innovation that would follow, reducing the risk of fire.

Though more convenient for refuelling, the location of these pumps proved disruptive to traffic flow. The earliest enclosed, drive-in gas stations were simple sheds. They exhibited little esthetic interest or uniformity in design and, as their numbers grew, they came under increasingly negative public scrutiny.

Prior to 1920, the curbside and shed-type stations tended to be in and around the central business district. I am sure that many of you will remember that in the 1940s and '50s the local gas stations were on Eagle Street, Davis Drive and most importantly, on Main Street.

As car ownership increased, oil companies began investing heavily in neighbourhood stations that would blend in with residential neighbourhoods. Many of these designs were domestic in inspiration and many of the buildings were prefabricated for convenience and economy.

Some companies began copying recognized architectural styles to establish their corporate identities. The basic domestic small house or cottage design was modified with the addition of a canopy. By 1925, most stations had grease pits and car washing floors.

The oil companies looked to past architectural styles for inspiration. A professional journal published in 1922 a feature article on four stations of "unusual and artistic design" in Vancouver featuring a modified California Mission motif. By the early 1920s, Imperial Oil began to build specific architect-designed stations and, by 1928, had adopted three standard plans for different urban contexts (business district, urban residential, small town and leased property).

By the 1930s, professional associations of architects had hopped aboard this new commercial landscape. By 1937, issues of the journal published by the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada were commenting on the unique requirements of the gas station and on its design challenges and suggesting a new approach to standard station design.

The economic depression of the 1930s brought about profound changes. Declining gasoline sales prompted many companies to expand their auxiliary product lines, necessitating larger display and storage spaces. They also began to emphasize automobile repair, which would require more and larger bays.

To attract customers, oil companies began to construct stations that were distinctly different. Rooflines became flat, offices were enlarged and integrated as an "oblong box" with rectangular perimeter dimensions. The amount of plate glass increased, and exterior decoration would decrease. The walls of stucco or brick were painted using specific company colours.

Terracotta was the most popular facing material in the 1930s, while porcelain enamel predominated in the 1940s and 1950s. These new gasoline stations followed the design style championed by the Bauhaus School in Germany. Out of the Great Depression in the 1930s and wartime rationing, came the oblong box design during the 1940s and 1950s.

In the 1960s, oil companies went back to the drawing board hoping to better blend into its environment, experimenting with new rooflines and materials.

It was in this period that there was a rise in independent dealerships with a simple small box design. Most of these dealers sold only gasoline and oil, along with cigarettes and soft drinks. The functional requirements were minimal, consisting primarily of office, storage, and rest room space. After 1960, the canopy was widely adopted by independents.

By 1970, new stations arose that consisted of vast canopies with small booths housing only the attendant and his cash register. Often rest room facilities and vending machines were in a separate building. They say that what is old is new again and these 1970s stations marked a return to the original filling station concept and were a result of higher gasoline prices in an era of supposed shortages.

Then by the late 1980s and into the 1990s, the self-service gas station dominated. The attached repair facilities gradually declined, likely due to more reliable cars, improved warranties, and growing popularity of specialty franchises such as muffler and oil change shops.

With their customers turning elsewhere for their repairs, companies had to find new methods to generate business. Sites now include both full and self-service pumps, convenience stores, fast food outlets, automated banking machines and other attractions.

The word "service" as a prefix for the gas station, which once indicated an expertise in specialized car repair and maintenance, had been redefined to mean one-stop shopping.

In the intervening years, those early stations have been reused or recycled. Their locations were highly desirable, having been located in urban areas with easy access. A problem frequently remains with their site contamination, necessitating the removal of the station infrastructure before the site can be repurposed.

As they disappear or perhaps morph into larger complexes, it is important that we recognize their place in our history and capture their unique designs for posterity.

Sources: The Gasoline Station, The Canadian Encyclopedia; The First Gas Station in Canada, The Vancouver Heritage Foundation; The History of Fuelling Up, Made In Canada Directory - Gas Stations, The History of Fuelling Up in Canada.

Newmarket resident Richard MacLeod, the History Hound, has been a local historian for more than 40 years. He writes a weekly feature about our town's history in partnership with Newmarket Today, conducts heritage lectures and walking tours of local interest, and leads local oral history interviews.