A young man with a buzz cut leans on a pristine countertop in a stark white kitchen and looks directly into the camera as he delivers what he presents as the secret to dating success for straight men.

"Finding a girl that will do whatever you want her to do," whether that's staying home or refraining from posting certain things online, is "easy," the man says confidently. Just give her financial security and don’t be ugly, he explains.

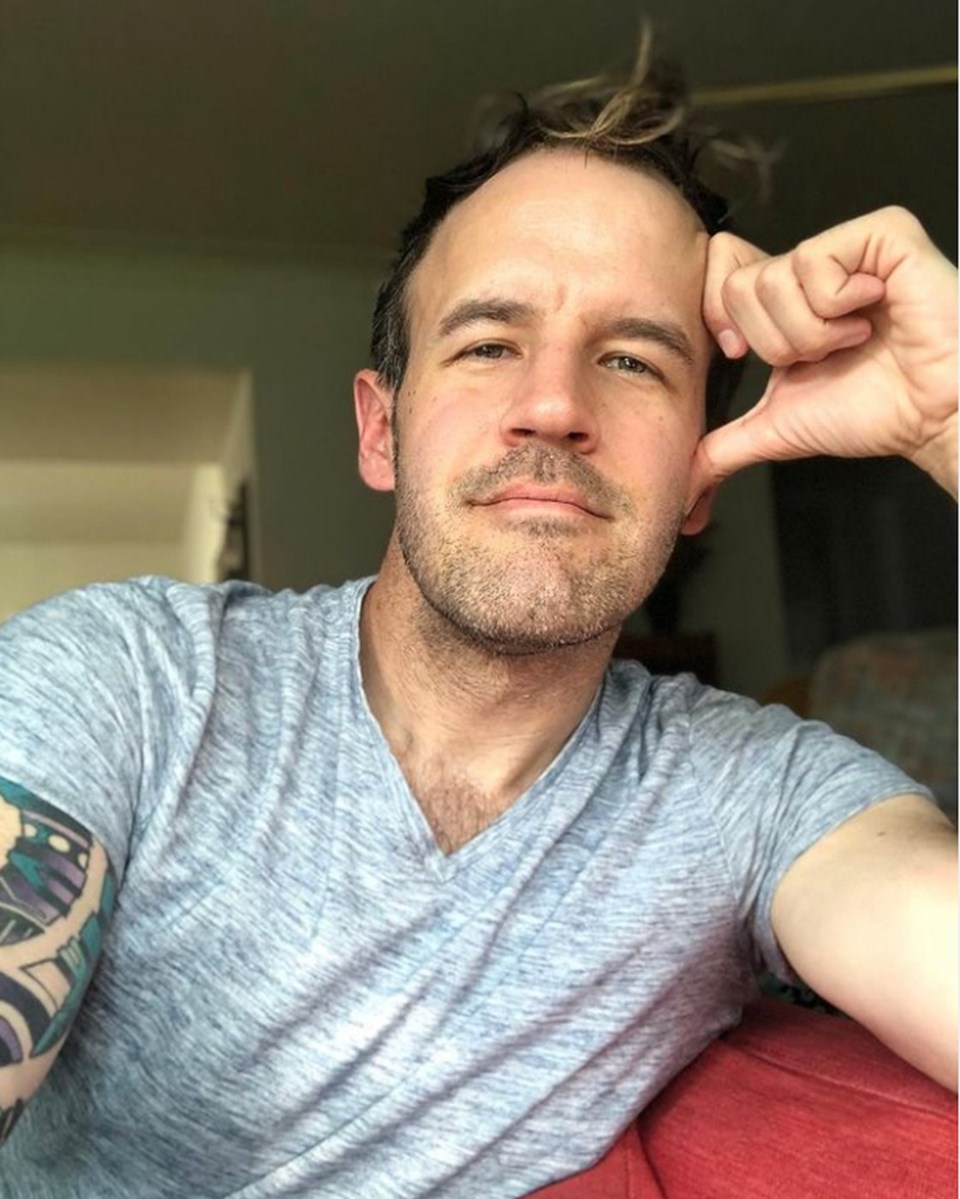

"Spoiler alert: that is, in reality, not it," Neil Shyminsky interjects in his video rebuttal of the young man's social-media post.

In between snippets of the original clip, Shyminsky, wearing a dark hoodie and rectangular glasses against a backdrop of loaded bookcases, recaps research on what women look for in romantic relationships before concluding that what the man is describing isn't, in fact, a girlfriend.

"She's financially dependent on you and has to be responsive to all your directives," he says. "Congratulations! You have an employee – and one hell of a toxic workplace."

Shyminsky's video, posted roughly a month ago, has drawn more than 10,000 likes on TikTok as well as reams of comments there and on Instagram, largely from people denouncing or making fun of the initial advice.

As misogynistic rhetoric fuelled by influencers such as Andrew Tate increasingly infiltrates daily conversations online and off, a small cohort of men is building a following on social media dismantling messages from the so-called manosphere, one meme and video stitch at a time.

Shyminsky, an English professor at a college in Sudbury, Ont., who goes by @professorneil on TikTok, picks apart popular videos and podcast excerpts multiple times a week for his hundreds of thousands of followers on various social media platforms.

There's an appetite for content that counters the surge in voices "pushing this very restrictive, frankly poisonous version of manhood," he said in a recent interview.

At the same time, "a bit of a vacuum" remains when it comes to offering alternative models of masculinity, "which is why it seemed so important," he said.

"I feel a moral imperative to be doing something," said Shyminsky, who joined TikTok three years ago as an outlet for overflow material from a course he taught on graphic novels before slowly switching gears.

Most of the videos Shyminsky critiques are sent to him by his followers – around 60 to 90 per cent of whom are women – depending on the platform, he said.

Sometimes his work makes its way to men and boys through the women in their lives, and Shyminsky joked he can tell when a video has been circulating that way from the sudden spike in angry messages from men.

But there are also messages of gratitude, he said.

"I've gotten a couple that are thank yous for demonstrating that this is something that men actually do notice and care about," he said.

"And then many from men who will say that something about a video or several videos of mine that they've seen helped to make them aware of something in their own behaviour that they hadn't recognized was harmful or toxic."

In recent months, Shyminsky has touched on issues such as division of labour in the home, gender reveal parties and sexist messaging around last month's U.S. election.

The election that cemented Donald Trump's comeback and the discourse around it show "it's never been more important than it is now to have these conversations," he said.

Misogynistic content, including calls to revoke women's right to vote, spiked online in the lead-up to the election, according to the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a group of independent, non-profit organizations focused on combating extremism and disinformation.

The use of the slogan "your body, my choice," popularized in part by white nationalist podcaster Nick Fuentes, jumped 4,600 per cent in a 24-hour span in the days following the Nov. 5 vote, the group said, though some of that was due to people speaking out against it.

The phrase also appeared to spread beyond the online realm, with parents and girls sharing accounts of off-line harassment, including incidents where it was chanted by boys in schools, the group said.

Educators have also been sounding the alarm in recent years over Tate's hold on young boys. The former kickboxer turned influencer, who is facing charges related to human trafficking and other offences in Romania, has millions of followers on X.

Despite being banned from most other major social media platforms, he remains a central figure in the manosphere, an assortment of online communities that range from anti-feminism to more overt violent rhetoric targeting women, including the "incel" or involuntary celibate subculture.

Historically, these spaces have been dominated and defined by men such as Tate who are "actually preying on vulnerabilities of other boys and men," said Michael Kehler, a research professor of masculinities studies in education at the University of Calgary's Werklund School of Education.

Proclamations that reinforce a specific type of traditional masculinity can appeal to some men and boys "who are feeling that there's multiple signals and multiple messages about masculinities, plural," he said.

Meanwhile, Shyminsky and his peers not only provide a more critical lens on masculinities but "they do so with a level of insight and in a way that's very Invitational and not belittling to their audience," he said.

Cyzor, another content creator with hundreds of thousands of followers on several platforms, said he makes an effort to answer questions sent in by young men, knowing they're likely based on misconceptions propagated by the manosphere.

A U.S. Navy veteran now living in Los Angeles and working as an intimate portrait photographer, Cyzor – who posts under @cyzorgg and asked not to be identified by name to protect his privacy – said he came to realize that his line of work and his close friendships with women gave him insights others may not have access to.

"Because a lot of guys don't listen to what women have to say or won't listen to things unless it's said by a guy, a lot of the information just doesn't connect," he said in a recent interview.

"And so I'm like, well, I know how to explain this stuff as well, and I also am a guy, so maybe they might be more inclined to listen to me.”

Humour also helps get the message across, because it's harder to argue with a joke, he said.

Many of the men who make this kind of content have crossed paths online, and sometimes collaborate or reference each other's work, he said.

"There's a growing number of us creators who are trying to be that difference, or try to show what that difference might look like and offer men an alternative way of thinking," he said.

Aside from teaching and making videos, Shyminsky is also working on a book aimed at young men.

The format is expected to be similar to "12 Rules For Life: An Antidote to Chaos," the self-help book written by controversial Canadian psychologist and commentator Jordan Peterson, whose messaging Shyminsky has repeatedly criticized.

"We can't ever take for granted that younger generations will figure it out, and that the information or the messaging is going to filter down to them organically," said Shyminsky, who has two daughters.

"So whatever we are doing, we need more people out there doing it. … I think that the next few years will go a long way toward showing us whether we have any chance of righting the ship."

— With files from The Associated Press.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Dec. 28, 2024.