Voting online or by telephone was easy enough, but the survey in which Newmarket residents were invited to participate after casting their ballots was “annoying”, “long”, “irrelevant” and “intrusive”, some voters say.

About a handful of citizens who completed the survey about their online voting experience in the Town’s first fully electronic election offered up their view in the 656-member Newmarket Votes Facebook group.

“I was annoyed with some of the questions about money, age and race,” said John Day, who started the conversation thread Oct. 20 on the popular page after he voted.

Nancy Fish responded with, “I regretted my decision (to do the survey) when it became too lengthy and was asking for my provincial political affiliations.”

Others chimed in that they decided not to participate or when there was a choice not to answer a specific question, they didn’t.

Of the 19,662 residents who voted in Newmarket's 2018 municipal election, 7,046 completed the survey, or 36 per cent, the Town confirmed.

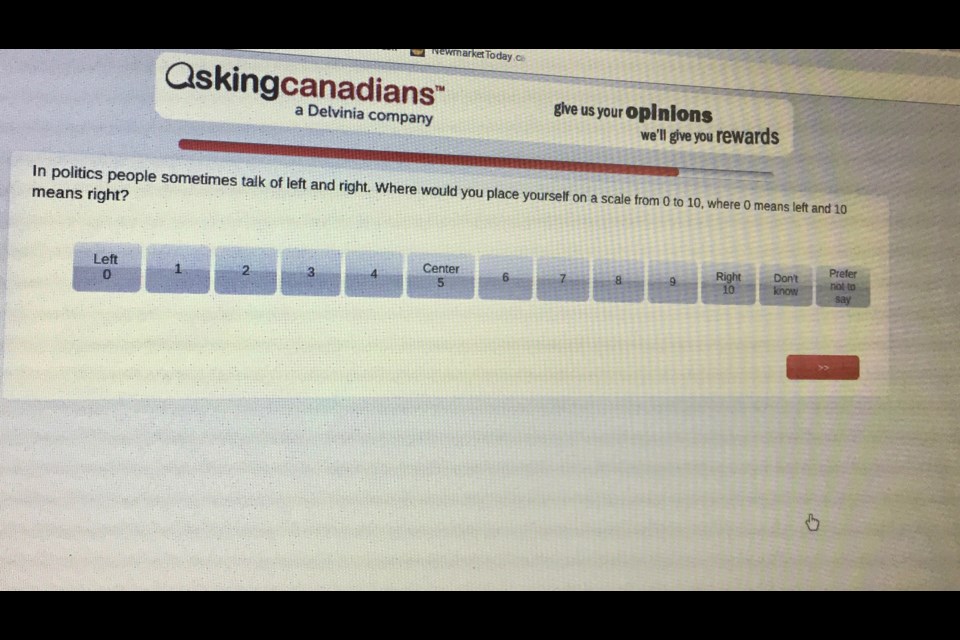

There were questions on the anonymous survey about paper voting versus electronic voting, and others that asked about such things as trust in government to do the right thing, political leanings, online activities, self-identification and disability status, and the type of home internet used.

But as more towns and cities in Ontario change things up for voters with a switch to electronic voting, it’s important to know how voters feel about the technology and to understand the impact on improving voter turnout, convenience and accessibility, said Nicole Goodman, an assistant professor of political science at Brock University who is the lead researcher and author of the survey.

“It’s important because internet voting is growing,” she said.

The number of municipalities that have gone digital each election cycle has skyrocketed in the last 16 years. In 2003, only 12 Ontario municipalities ran some form of electronic election. Today, 194 towns and cities, out of 414 that are in charge of running their own elections, have switched to internet voting.

Goodman, who also serves as director of the Centre for e-Democracy, said some of the survey questions are tried-and-true, classic questions used in voting surveys to gauge attitudes about a given subject. Conducting this type of research helps the centre to provide sound policy advice and best practices to municipalities as they implement electronic elections.

On the question of political leanings, Goodman said from a research standpoint, it’s crucial to know the types of voters who are attracted to online voting.

“Studies show that young people actually prefer traditional paper ballots because that’s connected to the first time they voted, and is a rite of passage for them,” Goodman said. “It’s a myth that seniors don’t like internet voting. The biggest users are voters over 50. In Truro, NS, a small community with a large senior population, when they went to a fully electronic election they saw a 140-per-cent participation increase.”

Newmarket’s first internet election will be featured as a case study in the Electronic Elections Project, which aims to gain a deep understanding of how voting online affects citizens, local elections, and democracy, led by principal investigator Goodman.

*Editor's note: This article was updated Oct. 24 to include the total number of surveys completed by Newmarket voters.