I have always been a keen observer of the various political cartoons that have graced our local newspapers and magazines. I have often wondered how it all began and just how they evolved into the fine art of depicting the odd points of political or public policy through the various character that become the butt of their satire.

I'll share what I discovered, beginning by defining what a political cartoon is and then examining the history of the political cartoon with an emphasis on Canada.

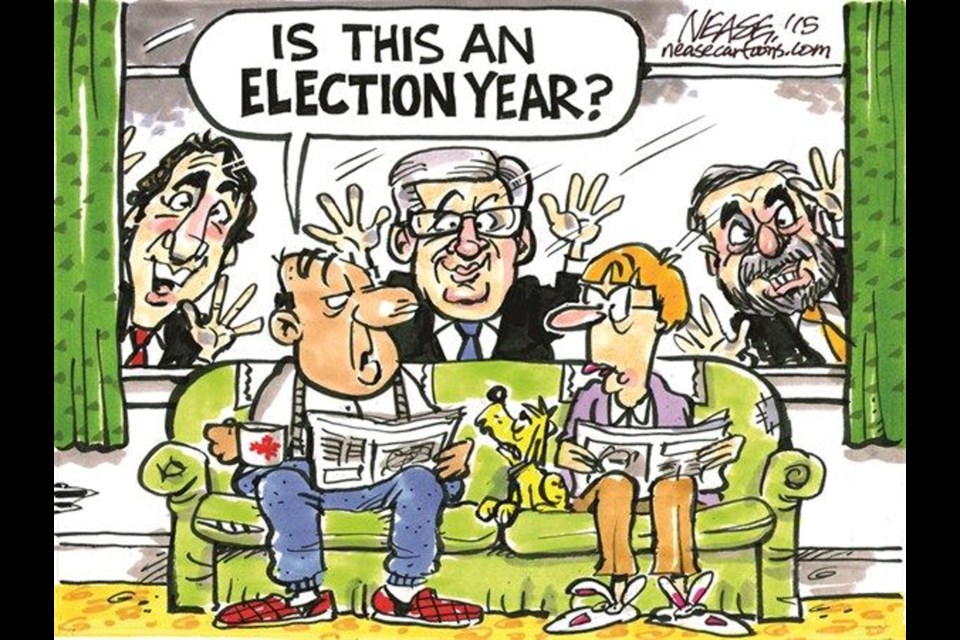

A political cartoon is an editorial rendering that uses graphics with caricatures of public figures to express an opinion about an event, policy or trend. The artist is known as an editorial cartoonist, combining artistic skill, a touch of hyperbole and the ability to satire or question authority to draw attention to corruption, political violence, and other social ills.

Developed in England in the latter part of the 18th century, the political cartoon was pioneered by James Gillray. At the time his and others in the flourishing English industry were often sold as individual prints in print shops. Founded in 1841, the British periodical Punch (which is where I first discovered the joy of the political cartoon) appropriated the term ‘cartoon’ to refer to its political cartoons, which was to lead to the term's widespread use world-wide.

John W. Bengough is credited with first perfecting the art of the political cartoon as we have come to know it in the 1870s when he started publishing his satirical magazine, Grip. In its pages, Bengough derided Canada's first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, and since then each successive prime minister has had an alter ego with a sketchpad: Sir Wilfrid Laurier had to contend with Henri Julien, Mackenzie King with Arch Dale, John Diefenbaker with Duncan Macpherson, Pierre Trudeau with Jean-Pierre Girerd, Brian Mulroney with Aislin (Terry Mosher), and Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin with Serge Chapleau.

The art is quite often fleeting, the artists needing to create a fresh set of caricatures daily, a fresh commentary on a current news event. Once the drawings appeared, they became as relevant as yesterday's newspaper. They are neither comic strips drawn to tell a story and get a chuckle, nor are they illustrations created by graphic artists. They often exceed the bounds of fair editorial comment and are usually drawn to make their subjects look ridiculous.

The first celebrated example in Canada was the work of Brigadier-General George Townshend, who served with General James Wolfe at Québec in 1759. Townshend seemingly drew sketches to undermine his commander's reputation. Wolfe would soon demand an inquiry, but he died on the Plains of Abraham.

It wasn't really until Punch in Canada arrived in the 1840s that editorial cartoons began to appear on a regular basis. Punch would hatch other homegrown publications such as Grinchuckle, Canadian Illustrated News, and L'Opinion Publique.

Canada soon produced its own political cartoon style. Working for the first comic journal in Québec, la Scie (the Saw), which began in 1863, cartoonist Jean-Baptiste Côté became legendary, combining his simple woodcuts with the motto Laughter Corrects Abuse. He became renowned for attacking the political elite and the civil service with such passion that in 1868, after he depicted a civil servant ‘at his day's work,’ he was arrested and thrown into jail, making him the first and only Canadian cartoonist to have achieved this distinction.

In 1877, Le Canard was published in Montreal by pioneer cartoonist Hector Berthelot. This publication, like many before it, was supported by editors and publishers who drew the cartoons themselves.

I am sure that we all wonder, when we see a particularly biting cartoon, how did they get away with printing that? Canadian cartoonists began to wield a great degree of independence, divorcing themselves from the art department and creating a separate editorial entity, becoming autonomous.

Stories abound about Duncan Macpherson not being afraid to challenge his editors, doing so on several occasions, threatening to get his way or quit. This arose out of MacPherson’s general distaste for editors. He had witnessed the poor treatment of his predecessor at the Toronto Star newspaper, Les Callan, who after 25 years was unceremoniously cast aside.

Before Macpherson, most cartoonists were a part of the paper’s editorial page team who decided what would go on the page that day. Macpherson refused to join the team or go to meetings and pressed to be given the status of an independent contributor to the editorial page.

For many years it was quite common for an editorial cartoon to contradict the stated editorial position of their newspaper. However, by the early part of 2000s, the position of staff cartoonist would come under increasing attack with chain newspapers beginning to eliminate staff positions, choosing to employ instead the less expensive freelancers, or using syndicates. In this way the cartoon could be "cherry picked" to coincide with the paper's position, a huge step backwards.

The growth of the internet brought the rise of the freelance cartoons now marketed worldwide by huge publishing syndicates. These sites serve as web portals where an editor or business could download fresh political cartoons, gag cartoons, caricatures, graphic art, and illustrations by a variety of cartoonists.

The best editorial cartoonists are members of a select club. There are no more than two dozen employed at any one time in Canada. My personal favorites where Duncan Macpherson with the Toronto Star and Andy Donato with the Toronto Sun. As I do a great deal of research for these articles in old Newmarket Eras, I have come to enjoy cartoons by Cargill and Stanley, which I believe were syndicated cartoonists of the time.

By 1949, cartoons had become so persuasive that the Canadian National Newspaper Awards decided to honour those that "embody an idea made clearly apparent, good drawing, and striking pictorial effect."

There are important institutions that house and glorify the art form around the world, Institutions like the Center for the Study of Political Graphics in the United States, and the British Cartoon Archive in the United Kingdom.

What about the modern political cartoons today? Political cartoons can usually be found on the editorial page of many newspapers, although a few (such as Garry Trudeau's Doonesbury) are sometimes mixed in with the regular comic strip page.

I love political cartoons because they contribute to political discourse enhancing political comprehension and laying bare events. From my travels I have discovered that there are no fundamental differences in the way Canadian political cartoonists and foreign political cartoons assess politics and public life.

A political cartoon works by drawing together two unrelated events and brings them together bizarrely for humorous effect. The humour can reduce people's political anger and so serve a useful purpose.

There can be controversies associated with political cartoons. We certain remember the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy and the Charlie Hebdo shooting (stemming from the publication of cartoons related to Islam).

And finally, I thought you may enjoy this primer on how to interpret and enjoy a political cartoon from a primary school lesson plan I found.

The students are first asked to examine the cartoon and use the questions included to help them decode the message of the cartoon. They are asked to be as specific as possible and include as many details as possible. They are asked to reference the aspects of the cartoon when answering the questions.

They are initially asked to glance at the cartoon and explain their first gut response. They are asked to consider their background knowledge such as what they already know about the context of the cartoon as to the time, place, situation, etc. How does the picture’s techniques help to present the message?

They are next asked to examine the text. How do the words, numbers, etc. in the drawing express ideas or identify people or objects? What message do the labels send to the readers?

They are asked to return to the characters and notice the people in the picture. How do their facial expressions (exaggerated, oversimplified, emotional features of the figures) add to the effect of the picture? What message does this send to the reader? They are asked to identify the symbols (clothing, religious, cultural, etc.). What do these signs or images represent? Is there a lack of symbols in the picture, why? How does this add to the message of the picture?

Finally, they are asked to draw some conclusions: What overall impression can you draw? Can they identify possible biases and decide whose perspective or point of view is expressed in the cartoon? They are asked to explain the overall message of the cartoon.

The political cartoon is seen as a valuable historical document, a signpost to what was important at that particular moment in time and the prevailing attitudes.

I suggest that next time you encounter a political cartoon, try to follow this exercise above, and see what effect the cartoon has on you. A well-crafted cartoon will move you in some way, no matter your personal feelings on the content.

Sources: The Art of Controversy: Political Cartoons and Their Enduring Power by Victor S. Navasky; The Political Cartoon by Charles Press; History of the Political Cartoon from Toons Mag; The power of cartoons, a TED Talk; Political Cartoons - Comprehensive guide to political editorial cartoons on the Web from About.com; The Hecklers: A History of Canadian Political Cartooning by Peter Desbarats and Terry Mosher; Grade 9 Social Studies Exercise - Political Cartoons by M. Dufresne.

Newmarket resident Richard MacLeod — the History Hound — has been a local historian for more than 40 years. He writes a weekly feature about our town's history in partnership with NewmarketToday, conducts heritage lectures and walking tours of local interest, and leads local oral history interviews.