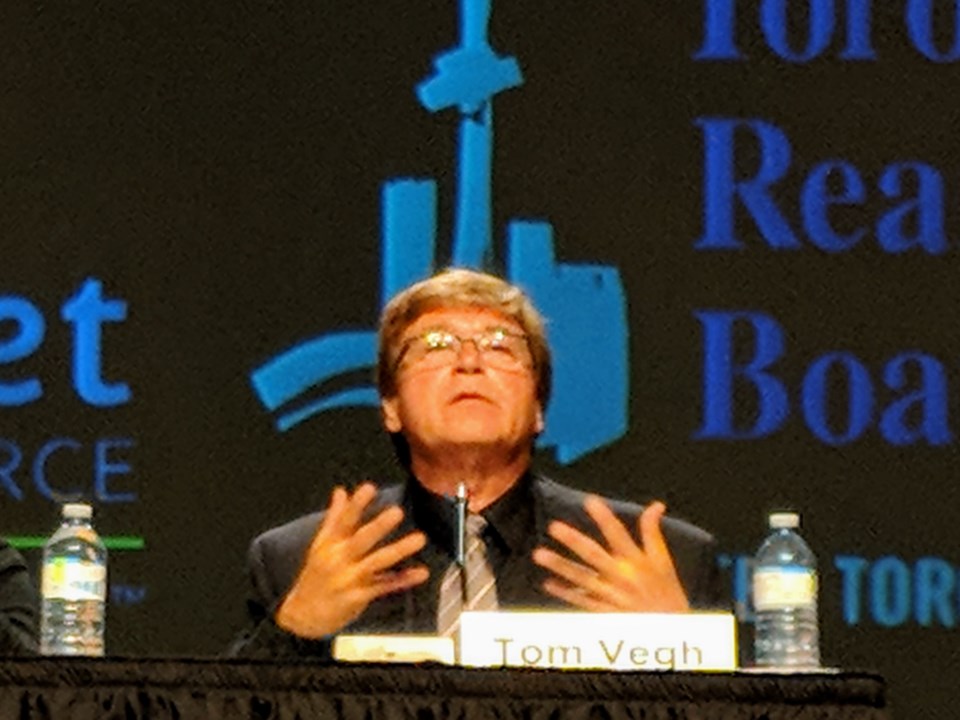

About 20 prominent York Region developers and others in the building industry made political donations totalling $22,850 to Newmarket Deputy Mayor and Regional Councillor Tom Vegh almost six weeks after the veteran local politician claimed a hard-fought victory in the Oct. 22, 2018 municipal election, campaign finance documents show.

Between Oct. 29, 2018 and Jan. 24, 2019, cheques from a veritable list of who’s who in the development community rolled into the Vegh campaign, the vast majority of which were for the $1,200 maximum donation allowable.

Donations were received from individuals who either head or work with York Region’s key residential and commercial land developers, including The Rose Corporation, which is building the 175 Deerfield Rd. residential development in Newmarket, Greenpark Group, Condor Properties, TACC Construction, Ballantry Homes, Bazil Developments, The Times Group, The Rice Group, who are building a hotel and retail/commercial complex at Davis Drive and Hwy. 404 in Newmarket, Stronach Group, CountryWide Homes, The Miller Group, and Groundswell Urban Planners, that counts among its achievements securing the land-use planning approvals for the 742-unit infill residential development known as the Glenway, according to the portfolio listed on its website.

More than half of Vegh’s campaign contributions came from individuals within the development industry, according to finance documents.

The four-term local politician who served as Newmarket’s Ward 1 councillor from 2006 to 2018, said the fact he was running town-wide increased his campaign costs substantially. For example, Vegh spent $45,420 on advertising, brochures/flyers and election signs, according to finance documents filed March 27, 2019.

Vegh took out a $27,800 personal line of credit and, due to election law limits on what a candidate can contribute themselves, filed a notice mid-November 2018 to extend the campaign period due to a deficit. That means a candidate can continue to fundraise to help pay down that debt until he or she is out of the red, or June 30, 2019, whichever comes first.

“In this case, I was in a situation where the most I could contribute myself still left me with about a $30,000 deficit, and you can’t finish a campaign with a deficit like that, otherwise it’s considered self-funding,” Vegh said. “So, after the election, I started receiving a lot of cheques and some of those I sent back for one reason or another, if I wasn’t comfortable accepting it. But there’s a few there that I said, ‘Yeah, OK’.”

“Developers are only a small portion of the donations I received,” Vegh said. “Most of the donations I got was after the election. I already won and they just started arriving in the mail. And I had to pay off that $30,000 deficit.”

The 2018 municipal election was the first to be conducted under significant reforms made to the Municipal Elections Act based on wide-ranging public consultations that eventually included a provincewide ban on corporate and union donations, among other things.

The spirit of that new provincial rule took particular aim at the land development industry, in part, due to the almost two decades of research by York University associate professor Robert MacDermid on the relationship between where development occurs and how much developers donate to local election campaigns.

In his 2016 submission to the province on the subject, the municipal government expert said: “In some municipalities, (development money) can be 60 per cent or 70 per cent of the money going to all of the candidates and, in some cases, it can be even higher for elected councillors. That’s a huge concentration of influence and, of course, what it ends up being is unregulated urban sprawl in many of those municipalities where development interests are greatest.”

“The problem of developer influence is compounded by external influence, as well,” MacDermid noted. “Many voters are now subject to support for councillors that comes from outside their community and that isn’t attentive to what community issues are about; it’s only concerned about development projects. I think that obviously distorts local democracy.”

While the corporate donation ban was lauded by democracy supporters, environmental groups and others, the move also raised maximum donations to $1,200, up from $750 and, of course, Ontario residents can personally make political donations to whomever they wish.

“For me, I’m looking that I can’t finish with a deficit. I won the election without their (developers) help, without even talking to them or them approaching me. And then we started receiving the donations,” said Vegh. “I’ve never even had developers come to try to persuade me of anything. It’s never even happened. We get staff reports on development, but I’ve never lobbied staff on behalf of anyone on anything. Not just on development, but on anything. We question staff reports, that’s our job and part of our due diligence. And, in the end, make a decision that’s in the best interest of the town.”

“You know, $1,200 or whatever someone is giving me, I don’t think that’s nearly enough to influence anyone in any corrupt way,” Vegh said. “Second, I’m not corrupt. Third, there’s an entire Newmarket council there, don’t overestimate my influence on council.”

Mayor John Taylor said he doesn’t necessarily believe campaign donations from the development community influences politicians, or that they are going to make different decisions based upon those contributions.

“I have not and I do not accept donations from developers, it’s a valuable practice for me, personally,” Taylor said, adding that he does not judge anyone else. “There’s great value in the public not seeing donations from developers to their elected officials, in terms of their trust level in those officials when it comes to land-use planning decisions.”

“I’ve sent cheques back in every election, including this one,” Taylor said, of the Oct. 22, 2018 municipal election.

Three-term incumbent Newmarket Councillor Jane Twinney spent $4,300 on her winning bid to be returned to council chambers.

According to campaign finance documents, about 75 per cent of Twinney’s $4,000 raised for her campaign was donated by individuals who work in the Region’s land development industry.

For example, Twinney received donations from individuals who head development companies that have built large commercial projects in Newmarket, including The Rice Group, development consultants Groundswell Urban Planners and United Soils Management.

“I accepted donations from anybody that didn’t have an ongoing development application before council and were more commercial in nature,” Twinney said. “A donation from a developer is not going to change my vote. I didn’t go out looking for (the donations), they approached me and they didn’t have any ongoing applications before the town.”

Incumbent Councillor Bob Kwapis spent the most of candidates campaigning for Newmarket council, with his successful bid coming with a $9,200 price tag. Kwapis, who also represents the town as a board director of its community-owned fibre optic company, Envi Network, raised $8,500 in donations. That support came mainly from the local Newmarket community, according to campaign documents.

Councillor Grace Simon’s first-time run at local politics cost her $7,000, less the $2,100 her campaign raised in donations.

Meanwhile, Councillor Victor Woodhouse largely self-funded his winning bid in last fall’s municipal election. Save for a single $300 donation, Woodhouse used his own funds to wage his $5,500 campaign.

Similarly, Councillor Trevor Morrison fully self-funded his campaign to the tune of $4,900, which is not uncommon among candidates vying for part-time councillor positions on local councils.

Incumbent councillors Kelly Broome and Christina Bisanz were acclaimed in the 2018 municipal election.

As the town’s No. 2 political boss, Vegh’s victory also gives him a seat at the Regional Municipality of York council table.

Deputy mayor and regional councillor-candidate Chris Emanuel on Dec. 31, 2018 filed a request to extend his campaign period due to a deficit.

Newmarket’s third challenger for the seat, Joan Stonehocker, who is executive director of the York Region Food Network and founder of Cycle Newmarket, spent about $3,200 on her campaign. She raised $550 in donations, and contributed $2,700 of her own money. Election signs claimed the largest portion of her election bid, coming in at $2,400.