The justice system is often in the news for the wrong reasons, and public concern is understandable.

Criminal cases inch along at a snail’s pace. People become disillusioned as to why those accused of serious crimes can end up on bail awaiting a months-in-the-future plea hearing or trial. Once convicted, some are re-released on existing bail conditions while they await sentence, even if everyone from the judge to the janitor knows they’re going down.

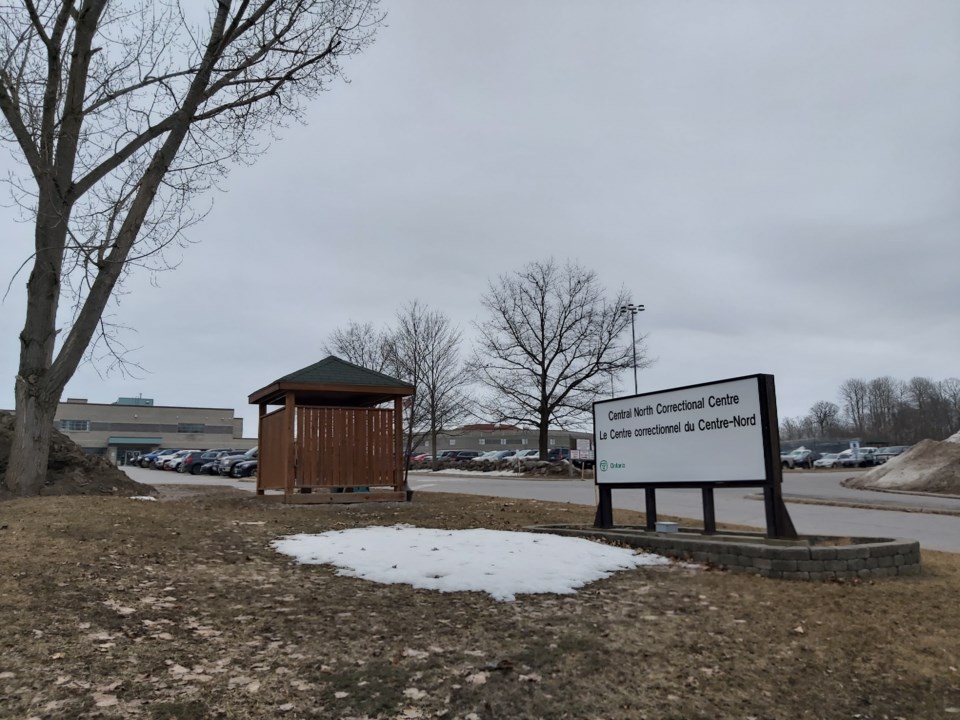

Locally, those not sprung on bail are housed at the Central North Correctional Centre (CNCC) in Penetanguishene. That often means being triple-bunked in a two-bed cell, forcing one prisoner to sleep on the floor with his head beside a toilet.

The reason for what ills CNCC is chiefly staffing and space. It’s none of the facility staff’s fault; it’s just that there is never enough of both.

These details are repeated like a mantra in pretty much every sentencing hearing that takes place at 75 Mulcaster St. in Barrie.

Every citizen in our area should care — better conditions for inmates generally lead to lower rates of reoffending upon release — but even if you don’t, the negative effects stretch far and wide.

Think about it as wanting to live in peace but without ever wanting to speak with your adversaries. Eventually, you have to suck it up and be a bigger person.

It’s time for the various stakeholders in the justice system to start talking and then do something about CNCC.

Consider the case of Michael Williams, the Country Lane shooter who was recently sentenced to seven years. The Crown attorney who prosecuted him, Indy Kandola, tried for three weeks to get CNCC staff to provide him with details of Williams’s 32 months in pre-sentence custody.

All Kandola got was crickets. The thought of a Crown lawyer being ignored by prison staff regarding a case where someone was shot is appalling.

Like all effective courtroom characters, Kandola has a certain presence about him. His body language says all you need to know, especially combined with his quick-fire, succinct manner. I like him for a few reasons, not least because he doesn’t mess around when it’s his turn to speak in court.

“Three weeks, your honour,” Kandola told Ontario Court Justice Cecile Applegate, his arms outstretched as if to represent the duration he waited to hear back and got nothing.

Applegate was equally unimpressed, calling the conditions at CNCC “shocking” when she passed sentence. She had little option as to how to apply pre-sentence credit except to do it on very favourable terms for Williams, especially considering the bad hand the institution dealt the Crown with its silence.

It’s not just Williams. Many criminals are now serving much shorter sentences than their actual terms. Enhanced credit and the magic 1.5:1 formula compared to actual time spent in pre-sentence custody means some are pleading guilty, happy to play the long game because they end up getting out sooner.

And then there is just the simple waste of time and public resources you witness every day at the courthouse.

On Friday, local lawyer Stephanie Marcade appeared by video waiting for a client’s case and for CNCC to bring him to its video suite. A few days earlier, his initial plea date had to be scrubbed because he was not brought at all. Marcade was on lunch from working a murder trial in Owen Sound and had to ad-lib because that courthouse’s Wi-Fi was on the fritz.

Marcade switched to her phone and waited patiently; another lawyer suddenly popped up on screen, apologizing for being about 20 minutes late because he was stuck in traffic. It was almost comic relief — by CNCC standards, he was early. The entire court eventually waited almost 45 minutes just to start.

With no hope the second case would be heard by the time CNCC had to turn off its feed due to staffing issues, that case was adjourned.

Marcade’s guilty plea on behalf of her client was snuck in and took about 15 minutes. Clad in her robes, a graceful presence even through a foggy iPhone camera, Marcade found a way to make it work despite the decidedly ungraceful conditions her client was living in and the hurried manner his case had to be heard.

It is just one small example of a much, much bigger problem that extends all the way up to the most serious matters before the courts.